The Nature of The Beast - Variations on a theme by Dante Alighieri

by Mike Nova

Divina Commedia

The Tragicomedy Most Prophetic

Трагикомедия Зело Пророческая

Inferno - The Hell - Ад

Canto I - The First Song - Песнь Первая

Inferno (Dante) - From Wikipedia

Inferno (Dante) - From Wikipedia

Inferno (Italian for "Hell") is the first part of Dante Alighieri's 14th-century epic poem Divine Comedy. It is followed by Purgatorio and Paradiso. It is an allegory telling of the journey of Dante through Hell, guided by the Roman poet Virgil. In the poem, Hell is depicted as nine circles of suffering located within the Earth. Allegorically, the Divine Comedy represents the journey of the soul towards God, with the Inferno describing the recognition and rejection of sin.[1]

*

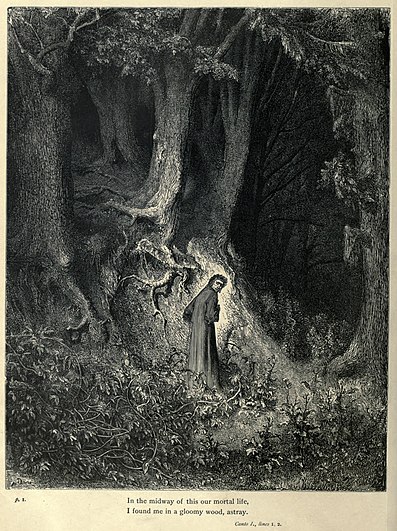

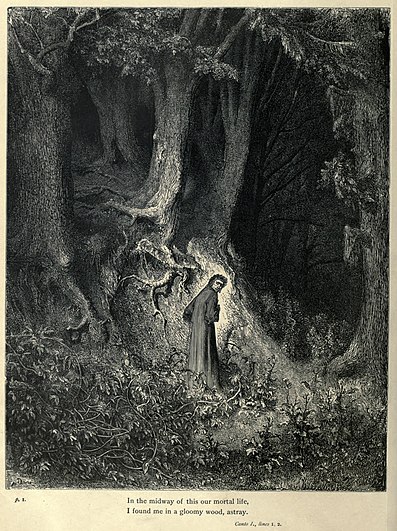

Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita

mi ritrovai per una selva oscura,

ché la diritta via era smarrita. 3

-

When I had crossed the midline of my life

the forest dark and dense embraced me tight,

I lost my ways which used to be direct.

-

Когда прошёл Я жизнь до середины

нашёл себя в лесу густом и тёмном,

свой путь Я потерял; прямым он был.

*

Io non so ben ridir com’i’ v’intrai,

tant’era pien di sonno a quel punto

che la verace via abbandonai. 12

-

Did not I see well the way I walked,

I was in trance at that most wretched point

at which I lost my ways.

-

И как Я заблудился, не заметил,

во сне Я был в тот самый тёмный час

когда Я потерял свой путь.

*

Poi ch’èi posato un poco il corpo lasso,

ripresi via per la piaggia diserta,

sì che ’l piè fermo sempre era ’l più basso. 30

-

To pause awhile, to rest my tired frame,

to climb again, up barren desert hill,

and yet to find my firm foot sliding down

-

Покой на миг, дай плоти отдохнуть,

чтобы опять на голый холм взобраться,

и вниз скользнуть, ногой одной лишь твёрдой.

*

una lonza leggera e presta molto,

che di pel macolato era coverta; 33

-

And look, at hill's foot, as the path my ends,

a Leopard, lean and with the spots all covered,

awaits me; many, many darkened spots;

-

А там, смотри; в подножиях холма,

поджался Леопард, тощо'й и быстрый,

и ждёт меня; в своих весь в пятнах чёрных;

*

l’ora del tempo e la dolce stagione;

ma non sì che paura non mi desse

la vista che m'apparve d'un leone. 45

-

The Beast, his skin in spots:

abandon all your hopes,

just angst alone when you behold The Lion.

-

Зловещий Зверь, в своей пятнистой коже;

надежды нет и ярость лишь одна

когда ты Льва увидишь.

*

Questi parea che contra me venisse

con la test’alta e con rabbiosa fame,

sì che parea che l’aere ne tremesse. 48

-con la test’alta e con rabbiosa fame,

sì che parea che l’aere ne tremesse. 48

He stood across directly and against me

his head high up, guts torn with raving hunger,

his vicious scream deaf pounding the air.

-

Напротив был он, прямо и готовно

и пасть развернута, терзает тело голод,

и рык его рвёт воздух к небесам.

*

Ed una lupa, che di tutte brame

sembiava carca ne la sua magrezza,

e molte genti fé già viver grame, 51

-

And then the She-Wolf, just the skin and bones

with cravings filled, in front of me transpired,

the misery and pain she brought to many.

-

Потом Волчица, кожа лишь да кости

передо мной внезапно появилась,

несчастья многие и многим принесла.

*

questa mi porse tanto di gravezza

con la paura ch’uscia di sua vista,

ch’io perdei la speranza de l’altezza 54

-

she burdened me

with terror of her sight,

and all the hopes of climbing back had perished

-

мой вольный дух она отяготила

одним лишь видом-ужасом своим,

и больше нет надежд на холм взобраться

*

E qual è quei che volontieri acquista,

e giugne ’l tempo che perder lo face,

che ’n tutti suoi pensier piange e s’attrista; 57

-

And so is he, who his will acquires

and time he gains; both doomed to loss,

for in his thoughts - just fear and despair

-

И вот он, тот, кто только что нашёл

и волю сладкую и связь времён, их должен потерять -

ведь в сердце - страх, а в мыслях - пустота.

*

tal mi fece la bestia sanza pace,

che, venendomi ’ncontro, a poco a poco

mi ripigneva là dove ’l sol tace. 60

-

and this was I, and ever restless Beast

did push me back, a step by little step

to place of darkness: sun dared not to speak.

-

и это Я был, потому что Зверь

меня назад толкал, ступеньку за ступенькой

пока Я не пришёл туда, где солнце немо.

*

Mentre ch’i’ rovinava in basso loco,

dinanzi a li occhi mi si fu offerto

chi per lungo silenzio parea fioco. 63

-

And while descended I to low depths,

before my very eyes he suddenly appeared

the one who seemed to be erased by silence

-

И лишь когда Я в самый в низ спустился

передо мною появился Он, тот самый, кто

молчанием своим казался стёрт навеки

*

Nacqui sub Iulio, ancor che fosse tardi,

e vissi a Roma sotto ’l buono Augusto

nel tempo de li dèi falsi e bugiardi. 72

-

"In Julius'es times was born I, although late,

in Rome I lived, in reign of good Augustus

in times of gods which were false and lying.

-

Родился Я под Юлием, и поздно;

и в Риме жил, Августом был приласкан

то были времена богов-подделок лживых.

*

Ma tu perché ritorni a tanta noia?

perché non sali il dilettoso monte

ch’è principio e cagion di tutta gioia?". 78

-

Why do you torture your own self and soul your own?

why climb we not up the Delightful Hill

the source and cause of joy, of all the joy?"

-

Ты почему пытаешь дух свой снова?

и почему б наверх нам не подняться

на Холм Заветный радостей всех главных?"

*

"Or se’ tu quel Virgilio e quella fonte

che spandi di parlar sì largo fiume?",

rispuos’io lui con vergognosa fronte. 81

-

"Aren't Virgil you, who is that font

of speech expanding like a river?",

I asked him, with my head in awe bowed

-

"Не ты ль Вергилий, о, не ты ль

фонтан речей, рекой текущих вольно?"

спросил Я тихо, головой склонившись

*

"O de li altri poeti onore e lume,

vagliami ’l lungo studio e ’l grande amore

che m’ ha fatto cercar lo tuo volume. 84

-

"You are the poets' honor and the light,

I studied you, to you I gave my love

For I explored your book without end.

-

"Поэтов всех ты честь и разум светлый

Тебе я посвятил учёбу долгую и любовь большую

Я в томе их твоём нашёл.

Vedi la bestia per cu’ io mi volsi;

aiutami da lei, famoso saggio,

ch’ella mi fa tremar le vene e i polsi". 90

-

Look at the Beast that turned me back;

Help me to fight Him, famous sage,

For blood my froze to ice and hands my tremble".

-

Ты видишь Зверя на пути моём;

Как мне сражаться с ним, мудрец великий,

Кровь холодеет и трясутся жилы".

* * *

"A te convien tenere altro vïaggio", 91

...

"se vuo’ campar d’esto loco selvaggio; 93

ché questa bestia, per la qual tu gride,

non lascia altrui passar per la sua via,

ma tanto lo ’mpedisce che l’uccide; 96

e ha natura sì malvagia e ria,

che mai non empie la bramosa voglia,

e dopo ’l pasto ha più fame che pria. 99

Molti son li animali a cui s’ammoglia,

e più saranno ancora, infin che ’l veltro

verrà, che la farà morir con doglia. 102

Questi non ciberà terra né peltro,

ma sapïenza, amore e virtute,

e sua nazion sarà tra feltro e feltro. 105

Ond’io per lo tuo me’ penso e discerno

che tu mi segui, e io sarò tua guida,

e trarrotti di qui per loco etterno; 114

ove udirai le disperate strida,

vedrai li antichi spiriti dolenti,

ch’a la seconda morte ciascun grida; 117

e vederai color che son contenti

nel foco, perché speran di venire

quando che sia a le beate genti. 120

...

ché quello imperador che là sù regna,

perch’i’ fu’ ribellante a la sua legge,

non vuol che ’n sua città per me si vegna. 126

In tutte parti impera e quivi regge;

quivi è la sua città e l’alto seggio:

oh felice colui cu’ ivi elegge!". 129

-

-

"You 'll choose another path

And leave this savage place

The beast does guard this pass

And blocks it shut with death

His nature squalid is, malicious, greedy;

He never sated gets,

Just hungrier.

He mates with many

And with many more he will

In all the types of dubious transactions

Until arrives The Dog

Who'll make him die in pain

Not on the land or bones

Does Dog this feed,

But wisdom, love and virtue

Are his food.

And Dog will hunt The Beast

Through every place, through every city and through every mind

Until he thrusts Him back to Hell

From which He came and was propelled by envy.

Then follow me, and I shall guide you then

From earthly place to the eternal one

You'll see there pain, you'll hear there howls

It's second death that they will go through

The souls which welcome burning fire

For it will cleanse them and purify the spirit

devoid of flesh unneeded

By fire christened and by fire lived

By fire saved, by fire resurrected,

By fire died, in old religious merger:

That's their hope to join the blessed.

And then, when you ascend as high as them,

Another guide will guide you forth instead

For I'll depart.

Because The Highest Ruler from above

Did ban me from His City

For I did not obey His Law.

He rules it all but rule He does from there,

Eternal city and the capital of His

Oh, lucky those are whom He allowed in.

"Oh poet, said I,

by this God you never knew,

I pray you:

Save me from this evil and the evils worse

And lead me to the place that you just mentioned

So I behold The Gateway of Saint Peter

And see those whom you described as pained".

And then he walked, I followed his path,

Direct and straight, as in days of past

And searching for the truth, the trip we started.

-

The fifth circle, illustrated by Stradanus

*

Links and References

dante alighieri biografia - GS

Dante Alighieri - W

Divina Commedia - W

wretched and divine - GS

-

Last Update: 8.26.13

Comments by the translator-author (Mike Nova):

This might appear as an entirely technical and medical comment, but it might be important for the understanding of the context. The Poet, Dante Alighieri, was probably deeply and clinically depressed by the "midline of his life" (early-mid 40-s?) and might had experienced vivid visual hallucinations ( e.g. "The Leopard" and "The She-Wolf"), possibly, and at least in part as a side effect of Digitalis, which might have been given to him for "heart ailment" which at those times (XII - XIII centuries) might not have been distinguished from the Depression itself as a specifically mental malady, without, necessarily a "heart ailment". One and the same phenomenon might be open to a variety of interpretations on the variety of levels of various observational modes, without excluding each other but completing the picture, as in this example, "the physical" and "the metaphysical, the poetic".

________________________________

Satan is trapped in the frozen central zone in the Ninth Circle of Hell, Canto 34

In the very centre of Hell, condemned for committing the ultimate sin (personal treachery against God), is Satan. Satan is described as a giant, terrifying beast with three faces, one red, one black, and one a pale yellow:

he had three faces: one in front bloodred;

and then another two that, just above

the midpoint of each shoulder, joined the first;

and at the crown, all three were reattached;

the right looked somewhat yellow, somewhat white;

the left in its appearance was like those

who come from where the Nile, descending, flows.[57]

Satan is waist deep in ice, weeping tears from his six eyes, and beating his six wings as if trying to escape, although the icy wind that emanates only further ensures his imprisonment (as well as that of the others in the ring). Each face has a mouth that chews on a prominent traitor. Brutus and Cassius are feet-first in the left and right mouths respectively, for their involvement in the assassination of Julius Caesar – an act which, to Dante, represented the destruction of a unified Italy and the killing of the man who was divinely appointed to govern the world.[58] In the central, most vicious mouth is Judas Iscariot, the namesake of Round 4 and the betrayer of Jesus. Judas is receiving the most horrifying torture of the three traitors: his head gnawed by Satan's mouth, and his back being forever skinned by Satan's claws. What is seen here is an inverted trinity: Satan is impotent, ignorant, and full of hate, in contrast to the all-powerful, all-knowing, and loving nature of God.[58]

The two poets escape Hell by climbing down Satan's ragged fur. They pass through the centre of the earth (with a consequent change in the direction of gravity, causing Dante to at first think they are returning to Hell). The pair emerge in the other hemisphere (described in the Purgatorio) just before dawn on Easter Sunday, beneath a sky studded with stars (Canto XXXIV).

-

-

THE SATURDAY ESSAY

'The Divine Comedy' is not just a classic of world literature. It's the most astonishing self-help book ever written

By

ROD DREHER

Updated April 18, 2014 11:45 a.m. ET

Dante's goal was 'to remove those living in this life from the state of misery and lead them to the state of bliss.' Above, 'Portrait of Dante Alighieri' by Attilio Roncaldier De Agostini/Getty Images

On the evening of Good Friday, a man on the run from a death sentence wakes up in a dark forest, lost, terrified and besieged by wild animals. He spends an infernal Easter week hiking through a dismal cave, climbing up a grueling mountain, and taking what you might call the long way home.

It all works out for him, though. The traveler returns from his ordeal a better man, determined to help others learn from his experience. He writes a book about his to-hell-and-back trek, and it's an instant best-seller, making him beloved and famous.

For 700 years, that gripping adventure story—"The Divine Comedy" by Dante Alighieri—has been dazzling readers and even changing the lives of some of them. How do I know? Because Dante's poem about his fantastical Easter voyage pretty much saved my own life over the past year.

Everybody knows that "The Divine Comedy" is one of the greatest literary works of all time. What everybody does not know is that it is also the most astonishing self-help book ever written.

It sounds trite, almost to the point of blasphemy, to call "The Divine Comedy" a self-help book, but that's how Dante himself saw it. In a letter to his patron, Can Grande della Scala, the poet said that the goal of his trilogy—"Inferno," "Purgatory" and "Paradise"—is "to remove those living in this life from the state of misery and lead them to the state of bliss."

The Comedy does this by inviting the reader to reflect on his own failings, showing him how to fix things and regain a sense of direction, and ultimately how to live in love and harmony with God and others.

This glorious medieval cathedral in verse arose from the rubble of Dante's life. He had been an accomplished poet and an important civic leader in Florence at the height of that city's powers. But he wound up on the losing side of a fierce political struggle with the pope and, in 1302, fled rather than accept a death sentence. He lost everything and spent the rest of his life as a refugee.

The Comedy, which Dante wrote in exile, tells the story of his symbolic death, rebirth and ascension to a higher state of being. It is set on Easter weekend to emphasize its allegorical connection with Christ's story, but Dante also draws on classical sources, especially Virgil's "Aeneid," as well as the Exodus story from the Bible.

Dante's masterpiece is an archetypal story of journey and heroic quest. Its message speaks to readers, whether faithful or faithless, who are searching for moral knowledge and a sense of hope and direction. In its day, it's worth recalling, the poem was a pop-culture blockbuster. Dante wrote it not in the customary Latin but in Florentine dialect to make it widely accessible. He wasn't writing for scholars and connoisseurs; he was writing for commoners. And it was a hit. According to the historian Barbara Tuchman, "In Dante's lifetime, his verse was chanted by blacksmiths and mule-drivers."

Who knew? Not me. I always thought "The Divine Comedy" was one of those lofty, doorstop-sized Great Books more admired than read. Its intimidating reputation is likely why few people ever walk with Dante through the fires of the Inferno, climb with him up the seven-story mountain of Purgatory and rocket with him through the stars to Paradise.

What a pity. They will never discover the surprisingly accessible beauty of Dante's verse in modern translation. Nor will they grasp how useful his poem can be to modern people who find themselves caught in a personal crisis from which there seems no escape. Dante's search for deliverance propels him on a purpose-driven pilgrimage from chaos to order, from despair to hope, from darkness to light and from the prison of self to the liberty of self-mastery.

Dante showed me how to do it too. Midway through my own life, my journey brought me back to my hometown, where, in the wake of my sister's death, I had hoped to start anew with my family. The tale of my sister Ruthie's grace-filled fight with cancer and the love of our hometown that saw her through to the end changed my heart—and helped to heal wounds from the teenage traumas that had driven me away.

But things didn't work out as I had expected or hoped. By last fall, I found myself struggling with depression, confusion and chronic fatigue—caused, according to my doctors, by deep and unrelenting stress. My rheumatologist told me that I had better find some way to inner peace or my health would be destroyed.

My guides were my priest, my therapist and, surprisingly, Dante Alighieri. Killing time in a bookstore one day, I read the first canto of "Inferno," in which the frightened and disoriented Dante comes to himself in the dark wood, all paths out blocked by savage animals.

Yes, I thought, that's exactly what this feels like. I kept reading and didn't stop. Several months later, after much introspective prayer, counseling and completing all three books of "The Divine Comedy," I was free and on the road to recovery. And I was left awe-struck by the power of this 700-year-old poem to restore me.

This will startle readers who think of "The Divine Comedy" only as the "Inferno" and think of the "Inferno" only as a showcase of sadistic tortures. It ispretty gory, but none of its gruesomeness is gratuitous. Rather, the ingenious punishments that Dante invents for the damned reveal the intrinsic nature of their sins—and of sin itself, which, as the poet says, makes "reason slave to appetite."

On the spiral journey downward into the Inferno, Dante learns that all sin is a function of disordered desire—a distortion of love. The damned either loved evil things or loved good things—such as food and sex—in the wrong way. They dwell forever in the pit because they used their God-given free will—the quality that makes us most human—to choose sin over righteousness.

The pilgrim's dramatic encounters in the "Inferno"—with tormented shades such as the adulterous Francesca, the prideful Farinata and the silver-tongued deceiver Ulysses—offer no simplistic morals. They are, instead, a profound exploration of the lies we tell ourselves to justify our desires and to conceal our deeds and motives from ourselves.

This opens the pilgrim Dante's eyes to his own sins and the ways that yielding to them drew him from life's straight path. The first steps to freedom require honestly recognizing that one is enslaved—and one's own responsibility for that bondage.

The second stage of the journey begins on Easter morning, at the foot of Mount Purgatory. Dante and his guide, the Roman poet Virgil, stagger out of the Inferno and begin the climb to the summit. If "Inferno" is about recognizing and understanding one's sin, "Purgatory" is about repenting of it, purifying one's will to become fit for Paradise.

Like all the redeemed souls beginning the ascent, Dante girds himself with a reed symbolizing humility. This is a truth every 12-stepper knows: Alone, we are powerless over our addictions.

But we aren't entirely powerless. On the Terrace of Wrath, where penitents must purge themselves, amid choking black smoke, of their tendency toward anger, the pilgrim meets a shade called Marco, whom he asks to explain why the world is in such a bad state. Marco sighs heavily and points to the poor choices that people make. "You still possess a light to winnow good from evil, and you have free will," Marco says. "Therefore, if the world around you goes astray, in you is the cause and in you let it be sought."

With these lines, the poet tells us to stop blaming other people for our problems. As long as we draw breath, we have it within ourselves to change.

Change is difficult and painful. But the penitents of Purgatory endure their purifications with joy because they know that they are ultimately heaven-bound. "I speak of pain," says a repentant glutton, now emaciated, "but I should say solace." The holy suffering of these ascetics unites them with Christ's example and sacrifice, which gives them the strength to bear it.

Dante's guide Virgil, who represents the best of human reason unaided by faith, can take the pilgrim to the mountaintop, but he cannot cross into Paradise. That task falls to Beatrice, the woman whom Dante had adored in life and in whose beautiful countenance young Dante saw a glimmer of the divine.

When he meets Beatrice at the summit, Dante confesses that after her death, he learned that he should set his heart on the eternal, on a love that cannot perish. But he forgot this wisdom and made his goal the pursuit of what Beatrice calls "false images of the good." This confession and his abject sorrow open the door for Dante's total purification, making him strong enough to bear the weight of heaven's glory.

"Paradise," which tracks Dante's rise with Beatrice through the heights of heaven, is the most metaphysical and difficult of the three books of "The Divine Comedy." It offers a vision of the Promised Land after the agonies of the purgatorial desert.

Allegorically, "Paradise" shows how we can live when we dwell in love, at peace with God and our neighbors, our desires not denied but fulfilled in harmonious order. It describes in rapturous passages how to be filled with the light and love of God, how to embrace gratitude no matter our condition and how to say, with the nun Piccarda Donati in an early canto, "In His will is our peace."

The effect all this had on me was dramatic. Without my quite realizing what was happening, "The Divine Comedy" led me systematically to examine my own conscience and to reflect on how I too had pursued false images of the good.

I learned how I had been missing the mark in my vocation as a writer. My eagerness to chase after new ideas before I had mastered old ones was a form of intellectual gluttony. The workaholic tendencies I considered a sign of my strong professional ethic were, paradoxically, a cover for my laziness; the more time I spent writing, the less time I had for the mundane tasks necessary for an orderly life.

Most important of all, reading Dante uncovered the sin most responsible for my immediate crisis. Family and home ought to have been for me icons of the good—that is, windows into the divine—but without meaning to, I had loved them too much, seeing them as absolute goods, thereby rendering them into idols. They had to be cast down, or at least put in their proper place, if I was going to be free.

And "The Divine Comedy" persuaded me that I was not helplessly caught by my failings and circumstances. I had reason, I had free will, I had the assistance of good people—and I had the help of God, if only I would humble myself to ask.

Why did I need Dante to gain this knowledge? After all, my confessor had a lot to say about bondage to false idols and about how humility and prayer can unleash the power of God to help us overcome it. And at our first meeting, my therapist told me that I couldn't control other people or events, but, by the exercise of my free will, I could control my response to them. None of the basic lessons of the Comedy was exactly new to me.

But when embodied in this brilliant poem, these truths inflamed my moral imagination as never before. For me, the Comedy became an icon through which the serene light of the divine pierced the turbulent darkness of my heart. As the Dante scholar Charles Williams wrote of the supreme poet's art: "A thousand preachers have said all that Dante says and left their hearers discontented; why does Dante content? Because an image of profundity is there."

That image is what Christian theologians call a "theophany"—a manifestation of God. Standing in my little country church this past January on the Feast of the Theophany, the poet's impact on my life became clear. Nothing external had changed, but everything in my heart had. I was settled. For the first time since returning to my hometown, I felt that I had come home.

Can Dante do this for others? Truth to tell, it is impossible for me, as a believing (non-Catholic) Christian, to separate my receptiveness to the poem from the core theological vision both Dante and I share.

But the Comedy wouldn't have survived so long if it were just an elaborate exercise in morality and Scholastic theology. The Comedy pulses with life, and it bears witness in its luminous lines and vivid tableaux to the power of love, the deathlessness of hope and the promise of freedom for those who have the courage to take the first pilgrim step.

Over Lent, I led readers of my blog on a pilgrimage through "Purgatory," one canto a day. To my delight, a number of them wrote afterward to say how much Dante had changed their lives. One reader wrote to say that she quit a three-decade smoking habit while reading "Purgatory" over Lent, saying that the poem helped her to think of her addiction as something that she could be free of, with God's help.

"I've had the sensation of maddeningly stinging, prickling skin during the nicotine withdrawal phase when I've tried to quit before," she said, "but reading Dante helped me to imagine the sensation as a cleansing fire."

Michelle Togut, a Jewish reader in Greensboro, N.C., told me that she was surprised by how contemporary the medieval Italian poet seemed. "For a work about what supposedly happens after you die, Dante's poem is very much about life and how we choose to live it," she said. "It's about spurning our idols and taking a long, hard look at ourselves in order to break out of the destructive behaviors that keep us from both G-d and the good life."

The practical applications of Dante's wisdom cannot be separated from the pleasure of reading his verse, and this accounts for much of the life-changing power of the Comedy. For Dante, beauty provides signposts on the seeker's road to truth. The wandering Florentine's experiences with beauty, especially that of the angelic Beatrice, taught him that our loves lead us to heaven or to hell, depending on whether we are able to satisfy them within the divine order.

This is why "The Divine Comedy" is an icon, not an idol: Its beauty belongs to heaven. But it may also be taken into the hearts and minds of those woebegone wayfarers who read it as a guidebook and hold it high as a lantern, sent across the centuries from one lost soul to another, illuminating the way out of the dark wood that, sooner or later, ensnares us all.

Mr. Dreher is a senior editor of The American Conservative, where portions of this essay first appeared. His most recent book, "The Little Way Of Ruthie Leming" (Grand Central), was published in paperback this week.