Last Update: 12.2.12

The great thinkers in quotes and comments

Reflections on "Meditations" of Marcus Aurelius - "The Notes To Myself"

Marcus Aurelius: emperor of the Roman world (161-180)

Biography

Nationality:Roman

Type:Soldier

Born:121

Died: 180

*

Meditations (Τὰ εἰς ἑαυτόν, Ta eis heauton, literally "thoughts/writings addressed to himself") is a series of personal writings by Marcus Aurelius, Roman Emperor 161–180 AD, setting forth his ideas on Stoic philosophy.

...

Structure and themes

The Meditations is divided into twelve books that chronicle different periods of Marcus's life. Each book is not in chronological order and it was written for no one but himself. The style of writing that permeates the text is one that is simplified, straightforward, and perhaps reflecting Marcus's Stoic perspective on the text. Depending on the English translation, Marcus's style is not viewed as anything regal or belonging to royalty, but rather a man among other men which allows the reader to relate to his wisdom.

A central theme to "Meditations" is to analyze your judgment of self and others and developing a cosmic perspective.

As he said "You have the power to strip away many superfluous troubles located wholly in your judgment, and to possess a large room for yourself embracing in thought the whole cosmos, to consider everlasting time, to think of the rapid change in the parts of each thing, of how short it is from birth until dissolution, and how the void before birth and that after dissolution are equally infinite".[2]

[Comment (M.N.):

To be humble in accepting the limits of understanding but bold in perspectives and wise in facing and confronting the vicissitudes of Life and The Unknown, and to keep a larger scale of things.]

He advocates finding one's place in the universe and sees that everything came from nature, and so everything shall return to it in due time. It seems at some points in his work that we are all part of a greater construct thus taking a collectivist approach rather than having an individualist perspective.

[Comment (M.N.):

It is always a continuum, as much and more than it is a dichotomy, just like many other conceptual "pseudodichotomies".]

Another strong theme is of maintaining focus and to be without distraction all the while maintaining strong ethical principles such as "Being a good man".[3]

[Comment (M.N.): The criteria for which, like with any other attempts at a definition of "man" are rather fluid; time, culture, class and group - bound, but do always exist as a working and "ideal" set.]

His Stoic ideas often involve avoiding indulgence in sensory affections, a skill which, he says, will free a man from the pains and pleasures of the material world. He claims that the only way a man can be harmed by others is to allow his reaction to overpower him.

[Comment (M.N.):

The notion of "overpowering" implies the issue of Power and the need to operationalise and to study this concept and phenomenon objectively, as well as the importance of ability for power over our own emotions, emotional reactions and overreactions.]

An order or logos permeates existence. Rationality and clear-mindedness allow one to live in harmony with the logos. This allows one to rise above faulty perceptions of "good" and "bad".

[Comment (M.N.):

Logos here is Law. Paradoxically, "living in harmony with the logos", "allows one to rise above faulty perceptions of "good" and "bad", as implied and incorporated into Logos - Law; it allows you to have your individual set of ethical perceptions and judgements about Laws, and to rise above (or potentially to stay below) the common, accepted and required sets of ethical perceptions and judgements.

In other words, as long as you stay within the law, you can think about it whatever you want.]

Meditations - From Wikipedia

*

Marcus Aurelius' Stoic tome Meditations, written in Greek while on campaign between 170 and 180, is still revered as a literary monument to a philosophy of service and duty, describing how to find and preserve equanimity in the midst of conflict by following nature as a source of guidance and inspiration. - W. (M.A.)

Quotations - ( Meditations - From Wikipedia )

- If thou art pained by any external thing, it is not this that disturbs thee, but thy own judgment about it. And it is in thy power to wipe out this judgment now. (VIII. 47, trans. George Long)

- A cucumber is bitter. Throw it away. There are briars in the road. Turn aside from them. This is enough. Do not add, "And why were such things made in the world?" (VIII. 50, trans. George Long)

- Soon you'll be ashes or bones. A mere name at most—and even that is just a sound, an echo. The things we want in life are empty, stale, trivial. (V. 33, trans. Gregory Hays)

- Never regard something as doing you good if it makes you betray a trust or lose your sense of shame or makes you show hatred, suspicion, ill-will or hypocrisy or a desire for things best done behind closed doors. (III. 7, trans. Gregory Hays)

- Not to feel exasperated or defeated or despondent because your days aren't packed with wise and moral actions. But to get back up when you fail, to celebrate behaving like a human—however imperfectly—and fully embrace the pursuit you've embarked on. (V. 9, trans. Gregory Hays)

- Let opinion be taken away, and no man will think himself wronged. If no man shall think himself wronged, then is there no more any such thing as wrong. (IV. 7, trans. Méric Casaubon)

- (...) As for others whose lives are not so ordered, he reminds himself constantly of the characters they exhibit daily and nightly at home and abroad , and of the sort of society they frequent; and the approval of such men, who do not even stand well in their own eyes has no value for him. (III. 4, trans. Maxwell Staniforth)

- Shame on the soul, to falter on the road of life while the body still perseveres. (VI. 29, trans. Maxwell Staniforth)

- Take away your opinion, and there is taken away the complaint, [...] Take away the complaint, [...] and the hurt is gone (IV. 7, trans. George Long)

- Whatever happens to you has been waiting to happen since the beginning of time. The twining strands of fate wove both of them together: your own existence and the things that happen to you. (V. 8, trans. Gregory Hays)

- Do not act as if thou wert going to live ten thousand years. Death hangs over thee. While thou livest, while it is in thy power, be good. (IV. 17, trans. George Long)

- Words that everyone once used are now obsolete, and so are the men whose names were once on everyone's lips: Camillus, Caeso, Volesus, Dentatus, and to a lesser degree Scipio and Cato, and yes, even Augustus, Hadrian, and Antoninus are less spoken of now than they were in their own days. For all things fade away, become the stuff of legend, and are soon buried in oblivion. Mind you, this is true only for those who blazed once like bright stars in the firmament, but for the rest, as soon as a few clods of earth cover their corpses, they are 'out of sight, out of mind.' In the end, what would you gain from everlasting remembrance? Absolutely nothing. So what is left worth living for? This alone: justice in thought, goodness in action, speech that cannot deceive, and a disposition glad of whatever comes, welcoming it as necessary, as familiar, as flowing from the same source and fountain as yourself. (IV. 33, trans. Scot and David Hicks)

- Do not then consider life a thing of any value. For look at the immensity of time behind thee, and to the time which is before thee, another boundless space. In this infinity then what is the difference between him who lives three days and him who lives three generations? (IV. 50, trans. George Long)

- When you wake up in the morning, tell yourself: The people I deal with today will be meddling, ungrateful, arrogant, dishonest, jealous, and surly. They are like this because they can't tell good from evil. But I have seen the beauty of good, and the ugliness of evil, and have recognized that the wrongdoer has a nature related to my own—not of the same blood or birth, but the same mind, and possessing a share of the divine. (II. 1, trans. Gregory Hays)

Meditations

The Thoughts of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus - General Index

Beautiful, the, ii. 1.

Circle, things come round in a, ii. 14.

*

Conquerers are robbers, x. 10

10. A spider is proud when it has caught a fly, and another when he has caught a poor hare, and another when he has taken a little fish in a net, and another when he has taken wild boars, and another when he has taken bears, and another when he has taken Sarmatians. Are not these robbers, if thou examinest their opinions?[7]

*

Co-operation. See Mankind and Universe.

*

On "Offenses through Desire" (Premeditated offenses) vs. "Offenses through Anger" (In a state of affect)

10. Theophrastus, in his comparison of bad acts—such a comparison as one would make in accordance with the common notions of mankind—says, like a true philosopher, that the offenses which are committed through desire are more blamable than those which are committed through anger. For he who is excited by anger seems to turn away from reason with a certain pain and unconscious contraction; but he who offends through desire, being overpowered by pleasure, seems to be in a manner more intemperate and more womanish in his offences. Rightly, then, and in a way worthy of philosophy, he said that the offence which is committed with pleasure is more blamable than that which is committed with pain; and on the whole the one is more like a person who has been first wronged and through pain is compelled to be angry, but the other is moved by his own impulse to do wrong, being carried towards doing something by desire.

Comments: Premeditated offenses.

*

Duty, all-importance of,

On Philosophy of Duty

vi. 2, 22;

2. Let it make no difference to thee whether thou art cold or warm, if thou art doing thy duty; and whether thou art drowsy or satisfied with sleep; and whether ill-spoken of or praised; and whether dying or doing something else. For it is one of the acts of life, this act by which we die; it is sufficient then in this act also to do well what we have in hand (vi. 22, 28).

22. I do my duty: other things trouble me not; for they are either things without life, or things without reason, or things that have rambled and know not the way.

x. 22

22. Either thou livest here and hast already accustomed thyself to it, or thou art going away, and this was thy own will; or thou art dying and hast discharged thy duty. But besides these things there is nothing. Be of good cheer, then.

*

The Thoughts of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus

by , translated by George Long

*

On Philosophy of Suicide - GS

Suicide, v. 29; viii. 47 (sub f.); x. 8 (l. 35)

29. As thou intendest to live when them art gone out, ... so it is in thy power to live here. But if men do not permit thee, then get away out of life, yet so as if thou wert suffering no harm. The house is smoky, and I quit it.[4] Why dost thou think that this is any trouble? But so long as nothing of the kind drives me out, I remain, am free, and no man shall hinder me from doing what I choose; and I choose to do what is according to the nature of the rational and social animal.

47. If thou art pained by any external thing, it is not this thing that disturbs thee, but thy own judgment about it. And it is in thy power to wipe out this judgment now. But if anything in thy own disposition gives thee pain, who hinders thee from correcting thy opinion? And even if thou art pained because thou art not doing some particular thing which seems to thee to be right, why dost thou not rather act than complain?—But some insuperable obstacle is in the way?—Do not be grieved then, for the cause of its not being done depends not on thee.—But it is not worth while to live, if this cannot be done.—Take thy departure then from life contentedly, just as he dies who is in full activity, and well pleased too with the things which are obstacles.

8. When thou hast assumed these names, good, modest, true, rational, a man of equanimity, and magnanimous, take care that thou dost not change these names; and if thou shouldst lose them, quickly return to them. And remember that the term Rational was intended to signify a discriminating attention to every several thing, and freedom from negligence; and that Equanimity is the voluntary acceptance of the things which are assigned to thee by the common nature; and that Magnanimity is the elevation of the intelligent part above the pleasurable or painful sensations of the flesh, and above that poor thing called fame, and death, and all such things. If, then, thou maintainest thyself in the possession of these names, without desiring to be called by these names by others, thou wilt be another person and wilt enter on another life. For to continue to be such as thou hast hitherto been, and to be torn in pieces and defiled in such a life, is the character of a very stupid man and one over-fond of his life, and like those half-devoured fighters with wild beasts, who though covered with wounds and gore, still intreat to be kept to the following day, though they will be exposed in the same state to the same claws and bites.[3] Therefore fix thyself in the possession of these few names: and if thou art able to abide in them, abide as if thou wast removed to certain islands of the Happy.[4] But if thou shalt perceive that thou fallest out of them and dost not maintain thy hold, go courageously into some nook where thou shalt maintain them, or even depart at once from life, not in passion, but with simplicity and freedom and modesty, after doing this one [laudable] thing at least in thy life, to have gone out of it thus. In order, however to the remembrance of these names, it will greatly help thee if thou rememberest the gods, and that they wish not to be flattered, but wish all reasonable beings to be made like themselves; and if thou rememberest that what does the work of a fig-tree is a fig-tree, and that what does the work of a dog is a dog, and that what does the work of a bee is a bee, and that what does the work of a man is a man.

*

Comments:

www.philosophy-dictionary.org/DutyCached

Marcus Aurelius Quotes with Mike Nova's Comments

Marcus Aurelius:

"The art of living is more like wrestling than dancing", or:

"Life is more a wrestling than a dance."

Comments:

Life is More The Wrestling Than The Dance

But most of all The Never Ending Trance.

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"Our life is what our thoughts make it."

Comments:

And our thoughts are shaped by our lives. It is a "hermeneutic" circle, a self-sustaining lifelong engine of knowledge.

__________________________________________________________________

Mike Nova shared Antinous the Gay God's photo. Thursday

Mike Nova shared Antinous the Gay God's photo. Thursday

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"When you arise in the morning, think of what a precious privilege it is to be alive - to breathe, to think, to enjoy, to love."

Comments:

Ah! Sounds like a wonderful and all natural antidepressant!

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"The happiness of your life depends upon the quality of your thoughts: therefore, guard accordingly, and take care that you entertain no notions unsuitable to virtue and reasonable nature."

Comments:

Therefore The Quality Control measures (for thoughts) should be introduced throughout the empire, to ensure that everyone "guards accordingly" and "no notions unsuitable to virtue and reasonable nature" are introjected in some unsuitable fashion into the very midst of the public intercourse. The problem is what to do with the bad thoughts, how to recycle them?

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"Very little is needed to make a happy life; it is all within yourself, in your way of thinking."

Comments:

H-h-h-m-m-m.

These days it is not that easy and is not "very little". But the principle is definitely correct.

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"The object of life is not to be on the side of the majority, but to escape finding oneself in the ranks of the insane."

Comments:

What is "the object of life", what is "the majority" and who are "the insane"?

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"Do every act of your life as if it were your last."

Comments:

And what should be the very last one?

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"Be content with what you are, and wish not change; nor dread your last day, nor long for it."

Comments:

Just "be content". Almost as in "just say no" or "just say yes". M.A. used opium freely. Would he be different if he did not? Would he think differently if he did not? Would he "be content" if he did not and how content? Would he have more chances to win the battle, or to loose it?

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"And thou wilt give thyself relief, if thou doest every act of thy life as if it were the last."

Comments:

The part about "giving thyself relief" sounds good.

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"Each day provides its own gifts."

Comments:

And its own pains. A fair mix.

*

On Death

Marcus Aurelius:

"It is not death that a man should fear, but he should fear never beginning to live."

Comments:

And some never do. Apropos, (just by the way), if the fear of life is the fear of death and vice versa,

then see the great formula of the great man.

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"Death is a release from the impressions of the senses, and from desires that make us their puppets, and from the vagaries of the mind, and from the hard service of the flesh."

Comments:

Cannot be said better. Death is just as natural as birth.

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"Despise not death, but welcome it, for nature wills it like all else."

Comments:

Nature certainly does. Do we "will it like all else"? And why "yes" and why "no", and how, and in what circumstances?

*

On Love

Marcus Aurelius:

"The sexual embrace can only be compared with music and with prayer."

Comments:

No comparisons would do; thank you, Marcus.

On Time

Marcus Aurelius:

"Confine yourself to the present."

Comments:

If you can confine yourself.

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"Never let the future disturb you. You will meet it, if you have to, with the same weapons of reason which today arm you against the present."

Comments:

A man and his weapon of reason against the Time: a war on the uncertainties of future and the need (very important and the strategic one) to prognosticate and forecast it and to build effective and practical cognitive models of it; to adapt and perfect the "arms of today".

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"Time is a sort of river of passing events, and strong is its current; no sooner is a thing brought to sight than it is swept by and another takes its place, and this too will be swept away."

Comments:

Sounds like NYC traffic.

*

On Mind, Soul and Character

Marcus Aurelius:

"Everything we hear is an opinion, not a fact. Everything we see is a perspective, not the truth."

Comments:

Good to know.

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"Dig within. Within is the wellspring of Good; and it is always ready to bubble up, if you just dig."

Comments:

I love mineral water.

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"Look within. Within is the fountain of good, and it will ever bubble up, if thou wilt ever dig."

Comments:

The "inside-diggers" of the world, ever misunderstood, downtrodden and outcast, unite!

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"You have power over your mind - not outside events. Realize this, and you will find strength."

Comments:

The powers "over your mind" and/or "outside events", just like the degree of "strength" and its sources - are all quite relative. The real questions are: What is Power? What is Strength? What is the true "typology" of "power" and "strength"; how are the different types of Power transformed and how do they interchange with each other, e.g.: military into political or diplomatic; or intellectual into scientific or religious, or spiritual, etc., etc. An important set of questions, if they can be answered usefully.

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"He who lives in harmony with himself lives in harmony with the universe."

Comments:

Very, very true. What remains is just to try to answer these questions: What is this "harmony"? And how to achieve it?

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"If it is not right do not do it; if it is not true do not say it."

Comments:

Good advice.

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"Here is the rule to remember in the future, When anything tempts you to be bitter: not, "This is a misfortune" but "To bear this worthily is good fortune.""

Comments:

This is one of the main ideas of stoicism: every crisis is a mother of opportunities.

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"Natural ability without education has more often raised a man to glory and virtue than education without natural ability."

Comments:

Attention, Educators!

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"Be content to seem what you really are."

Comments:

This is also an excellent advice, however "what you really are" might be many different things due to richness, complexity and "many-sidedness" of human nature and life.

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"Waste no more time arguing about what a good man should be. Be one."

Comments:

Now define "a good man" for me, please. I will consider all definitions.

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"The soul becomes dyed with the color of its thoughts."

Comments:

Emotionally: the affective component of our thoughts "colours" the soul, creates a certain mood. Very interesting, deep and truthful (self)observation: we feel how our thoughts make us feel. There is also, like in everything, another part of a "reflexive chain": the "colours" (emotions, affective state, the moods) of our souls do colour our thoughts, as if in balance and return - it is a "mutual wash". If soul is "healthy", and the most important factor here is a general physical health, it charges the thoughts in a more positive emotional light. This aphorism is also a beautiful and poetic metaphor: emotions as transferable "colours of a soul".

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"Such as are your habitual thoughts, such also will be the character of your mind; for the soul is dyed by the thoughts."

Comments:

Some more on the subject above, and beautifully phrased again.

*

On Society

Marcus Aurelius:

"That which is not good for the bee-hive cannot be good for the bees."

Comments:

Another pearl of social philosophy: If it is not "good" for a group, community or society, it cannot be "good" for an individual. If it is not "good" for General Motors, it cannot be "good" for John Doe who works for General Motors. Who defines the"good"? The experts.

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"Men exist for the sake of one another."

Comments:

Biologically, every organism "exists for the sake" of itself. Socially, and biopsychosocially, it is evident and true: men do "exist for the sake of one another", in various settings, degrees and circumstances. In its extreme this line of thought might lead to the totalitarian phrase of Hitler: "individual man is nothing, the State is everything". I am sure that Stalin would sign this "declaration of understanding" with his hands and feet.

Individual Man is everything, that is why his Society and his State are everything. It is always an emotional, rational and ethical balance. The stronger is the sense of individual freedoms the stronger are the society and the state as a whole.

*

On Designs of People's Actions

Marcus Aurelius:

"Let it be your constant method to look into the design of people's actions, and see what they would be at, as often as it is practicable; and to make this custom the more significant, practice it first upon yourself."

Comments:

Practice the analysis of The World, The Others and The Society and start where it should be started and where the starts of all starts are: with Self-Analysis.

*

On Beauty

Marcus Aurelius:

"Anything in any way beautiful derives its beauty from itself and asks nothing beyond itself. Praise is no part of it, for nothing is made worse or better by praise."

Comments:

Praise and/or its absence are irrelevant. Beauty is a thing in itself, freestanding, autochthonous, one of the kind, sui generis, puzzling and unattached to any function except one: the nature of man and his humanity. "The World will be saved by Beauty", said Dostoevsky. I say: It is the Beauty that makes man a man. Man is a "homo aestheticus" even more, and more importantly than he is a "homo sapiens": an animal which is able to perceive, appreciate, create and recreate Beauty. I do not think that anything close to it is present in the Animal Kingdom, and it is a cardinal and main distinction between the two, while the rudimentary and primitive, and not so primitive, forms of intelligence are present in it broadly. And I suspect that Beauty was and is the major engine of the evolution, if there is such a thing as "evolution".

On Power

Marcus Aurelius:

"Because your own strength is unequal to the task, do not assume that it is beyond the powers of man; but if anything is within the powers and province of man, believe that it is within your own compass also."

Comments:

I want "my own compass".

*

On History

Marcus Aurelius:

"Look back over the past, with its changing empires that rose and fell, and you can foresee the future, too."

Comments:

The Past is always, for many phenomena and for both individual and collective human histories, one of the very few windows and one of the very few indicators, and maybe one of the most accurate ones, of The Future.

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"Everything that happens happens as it should, and if you observe carefully, you will find this to be so."

Comments:

Maybe "so", but how do we really know "so", besides the reliance on our subjective observations, which are always prone to mistakes?

*

On Victory

Marcus Aurelius:

"The secret of all victory lies in the organization of the non-obvious."

Comments:

Which requires intelligence, foresight and organisational abilities.

*

On Crime

Marcus Aurelius:

"Poverty is the mother of crime."

Comments:

The oldest, shortest and the most accurate of all the sociological analyses in general and of crime in particular. Although we might say that the picture might be a bit more complex than this one sentence and crime is the product of the promiscuous interactions of many putative parents, social underclass status and social disintegration do have one of the most valid claims to maternity.

*

On Nature

On Desires

On Anger

Marcus Aurelius:

"How much more grievous are the consequences of anger than the causes of it."

Comments:

We need the good anger managers: to master the art. (Although not necessarily the Jack Nicholson type).

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"The best revenge is to be unlike him who performed the injury."

Comments:

That's how the subversive christian ideology wormed its way up to the highest ranks of the empire and eventually destroyed the both. However I see some strategic and tactical aspects there, besides the ethical ones. The goal is to read the fine print and in between the lines.

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"Anger cannot be dishonest."

Comments:

Beautifully put, but incorrect. The true, honest anger arises from the depths of mixed and very strong emotions and indeed cannot in this case be "dishonest". But "dishonest", faked anger is practiced relatively often in various social interactions as an instrument of social domination and control. M.A. was too high up and too great to have a need for this instrument and this might be the reason why he discounted the possibility of "dishonest anger" in humans and in their varieties and in their various interactions.

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"Reject your sense of injury and the injury itself disappears."

Comments:

Because like many other things it is "in an eye of the beholder", and is a subject to (self)perceptions and (self)conceptualisations.

*

On Men

Marcus Aurelius:

"Accept the things to which fate binds you, and love the people with whom fate brings you together, but do so with all your heart."

Comments:

Otherwise they will not love you with all their hearts, which is somewhat less than desirable.

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"Adapt yourself to the things among which your lot has been cast and love sincerely the fellow creatures with whom destiny has ordained that you shall live."

Comments:

What if you got captured and sold into slavery? Is not death the "suitable" adaptation in these and similar circumstances and is it not then the "manifest destiny" and the "categorical imperative"? For the second part, see the previous comment.

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"A man's worth is no greater than his ambitions"

Comments:

And since "a man's ambitions" are always an exaggerated version of his "self-worth", the issue is the method and the system for the measurement of both; which can help to get a true picture or its closest approximation and will guard against the mismeasure of men and their ambitions.

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"A noble man compares and estimates himself by an idea which is higher than himself; and a mean man, by one lower than himself. The one produces aspiration; the other ambition, which is the way in which a vulgar man aspires."

Comments:

I guess, "vulgar men" have many different and "sophisticated" ways to "aspire". It is probably an evolutionary thing, "down to earth" capacity for adjustment, which "the earth" due to its eternally downward position, tends to positively condition.

"Ambition" is the "vulgar man's" "aspiration". The fundamental question is: what makes "a noble man" and what makes his "vulgar" counterpart, and how do they and their "aspirations" and "ambitions" intersect and interact?

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"I have often wondered how it is that every man loves himself more than all the rest of men, but yet sets less value on his own opinions of himself than on the opinions of others."

Comments:

This is the essence of "crowd psychology". The "majority" is the "followers" of various persuasions, stripes and shades, classified by timing of their responses into the:early, average and the late ("laggers") - stages. They feel more "comfortable and secure" in suppressing, relinquishing or significantly diminishing the sense, the scope and executability of their individual mentality and capacity for decision making and surrendering them to the "herd" and becoming a part of the "herd", sometimes with "or else".

Furthermore, this type of a "herd mentality" is rewarded by various kinds of "herdy" kudos and is "pseudo - herdo - kudo - adaptational".

The questions are: What degree of a "herd mentality instinct" should be allowed into the considerations of efficient management of the services and should be considered to be "healthy" ("ideal", "optimally operationally cohesive", etc., depending on the angles and the points of views). Apparently, in practice this issue is regulated by the complex interactions of the common elements and factors, such as structure and goals and the peculiarities of Times and Cultures. The specific variables and their measurements should be studied and their significance in various situations should be evaluated.

"Opinions of others" serve as a very powerful feedback mechanism in feeding and sustaining the "narcissistic well" (including its customary and "healthy" dimensions).

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"Let men see, let them know, a real man, who lives as he was meant to live."

Comments:

Free them, give them the basic necessities of life and good education and you might see them blossom. Which however will not automatically prevent humans from killing each other and other "mortal sins", all these "antisocial behaviors" are apparently a some part, natural or otherwise, of human nature also.

*

Marcus Aurelius:

"A man should be upright, not be kept upright."

Comments:

Of course it does not make any sense to try to keep upright the dead or morally dead body. However the "Uprightness" (the strength of character, a "backbone") is as much of a skill as it is a personality trait which might or might not be expressed properly or freely; life is too complex for "yes - no" answers, as the notion of Uprightness presupposes by its definition. And if it is at least half, if not all of a skill, it can and should be learned, taught and trained.

*

*

On "Altruism"

Marcus Aurelius:

"We ought to do good to others as simply as a horse runs, or a bee makes honey, or a vine bears grapes season after season without thinking of the grapes it has borne."

Comments:

"Altruism" (including the broad and various concepts of human nature and the nature of "humanity") is innate to human social nature and is a very important part of it. Due to the intricacies of "life struggle" (e.g. "class" and many other types of "struggles") this notion does not penetrate the usual human mind too deeply and is balanced by its opposite on the other side of the spectrum: "self-centerdness" ("preservation", "survival" instincts, etc.). The interesting twist in this, one of M.A.'s little gems of a thought is the emphasis on "naturalness", the "natural" quality of the so called "altruism" (for the lack of better and more accurate term); it is and should be just as simple and natural as a run of a horse, honey from bees or grapes from vine.

References and Links

Marguerite Yourcenar (8 June 1903 – 17 December 1987) was a Belgian-born French novelist and essayist. Winner of the Prix Femina and the Erasmus Prize, ...

Jump to: navigation, search

| Marguerite Yourcenar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Marguerite Antoinette Jeanne Marie Ghislaine Cleenewerck de Crayencour 8 June 1903 Brussels, Belgium |

| Died | 17 December 1987 (aged 84) Northeast Harbor, Maine, USA |

| Occupation | Author, essayist, poet |

| Nationality | French |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Notable work(s) | Mémoires d'Hadrien |

| Notable award(s) | Erasmus Prize (1983) |

| Partner(s) | Grace Frick (1903-1979) |

*

Mémoires d'Hadrien (1951) - translated Memoirs of Hadrian (by Grace Frick), ISBN 0-14-018194-6

marguerite yourcenar memoirs of hadrian - GS

*

Portrait of Power Embodied in a Roman Emperor

By JOSEPH EPSTEIN

In 1982, when I first read Marguerite Yourcenar's "The Memoirs of Hadrian," I asked Arnaldo Momigliano, the great scholar of the ancient world, what he thought of the novel. Italian to the highest power, he put all five fingers of his right hand to his mouth, kissed them, and announced, "Pure masterpiece." Now, nearly 30 years later, I have reread the work and find it even better than before. A book that improves on rereading, that seems even grander the older one gets—surely, this is yet another sign of a masterpiece.Its author was born in Belgium, wrote in French, and lived much of her adult life in Maine with her excellent translator and companion, Grace Frick. As such, Mme. Yourcenar (1903-1987) was, in effect, a writer without a country, though she was the first woman elected to the Académie Française (in 1980). She was the last aristocratic novelist of the 20th century, and not only in the sense that her father was of aristocratic descent. She did not ask in her fiction the contemporary middle-class questions of what is happiness and why have I (or my characters) not found it, concerning herself instead with something larger—the meaning of human destiny as it plays out on a historical stage.

Mme. Yourcenar wrote a good deal of fiction, but her imperishable work is "Memoirs of Hadrian," first published in French in 1951. The novel is in the form of a lengthy letter written by the aged and ill Emperor Hadrian, who ruled from A.D. 117 to 138, to the 17-year-old but already thoughtful Marcus Aurelius.

Roman emperors seem to be divided between monsters and mediocrities, with an occasional near-genius, like Hadrian, thrown in to break the monotony. Highly intelligent and cultivated, he was a Grecophile, always a good sign in the ancient world. As emperor, he attempted to pull back from the imperialist expansion of his predecessor Trajan and wanted, as the chronicler Aelius Spartianus put it, to "administer the republic [so that] it would know that the state belonged to the people and was not his property."

And yet Hadrian was also a Roman emperor, which meant living amid dangerous intrigue, wielding enormous power and being able to fulfill his erotic impulses at whim. He was, Spartianus writes, "both stern and cheerful, affable and harsh, impetuous and hesitant, mean and generous, hypocritical and straightforward, cruel and merciful, and always in all things changeable"—in short, not a god but a man.

Mme. Yourcenar has taken what we know of the life of Hadrian and from this sketchy knowledge produced an utterly convincing full-blown portrait. One feels that one is reading a remarkable historical document, an account of the intricate meanings of power by a man who has held vast power. Imagine Machiavelli's "The Prince" written not by an Italian theorist but by a true prince. Imagine, further, that he also let you in on his desires, his fears, his aesthetic, his sensuality, his feelings about death—in a manner at once haute and intimate, and in a prose any emperor would be pleased to possess.

"I see an objection to every effort toward ameliorating man's condition, on earth," Hadrian writes, setting out the political philosophy that will inform his reign, "namely that mankind is perhaps not worthy of such exertion. But I meet the objection easily enough: so long as Caligula's dream remains impossible of fulfillment, and the entire human race is not reduced to a single head destined for the axe, we shall have to bear with humanity, keeping it within bounds but utilizing it to the utmost; our interest, in the best sense of the term, will be to serve it."

Part of the mastery of "Memoirs of Hadrian" is in its reminder that the emperor, like the rest of us, remains imprisoned in a perishable human body. Hadrian's letter to young Marcus is being written at the end of his life, and so with a sure grasp of the inexorability of "Time, the Devourer." Hadrian has come into his wisdom only after manifold errors and tragic mistakes; not least among the latter, contriving, through thoughtlessness, in the death of his great love, the Bithynian youth Antinous. He is writing "when my harvests are in." The letter lets Hadrian take his own measure.

"I liked to feel that I was above all a continuator," Hadrian writes. He notes that he looked "to those twelve Caesars so mistreated by Suetonius," in the hope of emulating the best of each: "the clear-sightedness of Tiberius, without his harshness; the learning of Claudius without his weakness; Nero's taste for the arts, but stripped of all foolish vanity; the kindness of Titus, stopping short of his sentimentality; Vespasian's thrift, but not his absurd miserliness."

Mme. Yourcenar has Hadrian compare himself, favorably, with Alcibiades, who "had seduced everyone and everything, even History herself." Unlike Alcibiades, who had brought destruction everywhere, he, Hadrian, "had governed a world infinitely larger...and had kept pace therein; I had rigged it like a fair ship made ready for a voyage which might last for centuries; I had striven my utmost to encourage in man the sense of the divine but without at the same time sacrificing to it what is essentially human. My bliss was my reward."

Like most of our lives, Hadrian's—and so Mme. Yourcenar's novel—is plotless. What keeps the reader thoroughly engaged is not drama but the high quality of Hadrian's thought and powers of observation. Hadrian, through the sheer force of his mind, comes alive. That this most virile of characters has been written by a woman might be worth remarking were it not the case that the greatest novelists have always been androgynous in their powers of creation. With the dab hand of literary genius, Mme. Yourcenar has taken one of the great figures of history and turned him into one of the most memorable characters in literature in a masterpiece too little known.

—Mr. Epstein's latest book is "The Love Song of A. Jerome Minkoff and Other Stories" (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt).

*

hadrian - GS

www.amazon.com › Books › Biographies & Memoirs › HistoricalCached - Similar

Although his decision to abandon the expansionist policies of his predecessors seemed to forecast the Roman Empire's decline, this evenhanded biography ... hadrian quotes - GS

*

From Wikisource

| The Thoughts Of The Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus by , translated by George Long * Articles on Ancient History * Human self-reflection

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This penultimate scene of the Admonitions Scroll shows a palace lady sitting in quiet contemplation, presumably following the admonitions in the accompanying lines:[1] "Therefore I say: Be cautious and circumspect in all you do, and from this good fortune will arise. Calmly and respectfully think about your actions, and honor and fame will await you."

Human self-reflection is the capacity of humans to exercise introspection and the willingness to learn more about their fundamental nature, purpose and essence. The earliest historical records demonstrate the great interest which humanity has had in itself. Human self-reflection invariably leads to inquiry into the human condition and the essence of humankind as a whole.[citation needed]

Human self-reflection is related to the philosophy of consciousness, the topic of awareness, consciousness in general and the philosophy of mind.[citation needed]

*

Modern era The Enlightenment was driven by a renewed conviction, that, in the words of Immanuel Kant, "Man is distinguished above all animals by his self-consciousness, by which he is a 'rational animal'." In the 19th century, Karl Marx defined man as "labouring animal" (animal laborans) in conscious opposition to this tradition. In the early 20th century, Sigmund Freud dealt a serious blow to positivism by postulating that human behaviour is to a large part controlled by the unconscious mind.[citation needed] [edit] Comparison to other speciesVarious attempts have been made to identify a single behavioural characteristic that distinguishes humans from all other animals. Many anthropologists think that readily observable characteristics (tool-making and language) are based on less easily observable mental processes that might be unique among humans: the ability to think symbolically, in the abstract or logically, although several species have demonstrated some abilities in these areas. Nor is it clear at what point exactly in human evolution these traits became prevalent. They may not be restricted to the species Homo sapiens, as the extinct species of the Homo genus (e.g. Homo neanderthalensis, Homo erectus) are believed to also have been adept tool makers and may also have had linguistic skills.[citation needed]In learning environments reflection is an important part of the loop to go through in order to maximise the utility of having experiences. Rather than moving on to the next 'task' we can review the process and outcome of the task and - with the benefit of a little distance (lapsed time) we can reconsider what the value of experience might be for us and for the context it was part of.[citation needed] See also * Philosophy of mind

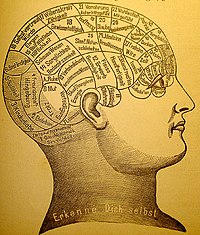

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A phrenological mapping[1] of the brain. Phrenology was among the first attempts to correlate mental functions with specific parts of the brain.

Dualism and monism are the two major schools of thought that attempt to resolve the mind-body problem. Dualism can be traced back to Plato,[3] and the Sankhya and Yoga schools of Hindu philosophy,[4] but it was most precisely formulated by René Descartes in the 17th century.[5] Substance Dualists argue that the mind is an independently existing substance, whereas Property Dualists maintain that the mind is a group of independent properties that emerge from and cannot be reduced to the brain, but that it is not a distinct substance.[6] Monism is the position that mind and body are not ontologically distinct kinds of entities. This view was first advocated in Western philosophy by Parmenides in the 5th century BC and was later espoused by the 17th century rationalist Baruch Spinoza.[7] Physicalists argue that only the entities postulated by physical theory exist, and that the mind will eventually be explained in terms of these entities as physical theory continues to evolve. Idealists maintain that the mind is all that exists and that the external world is either mental itself, or an illusion created by the mind. Neutral monists adhere to the position that there is some other, neutral substance, and that both matter and mind are properties of this unknown substance. The most common monisms in the 20th and 21st centuries have all been variations of physicalism; these positions include behaviorism, the type identity theory, anomalous monism and functionalism.[8] Most modern philosophers of mind adopt either a reductive or non-reductive physicalist position, maintaining in their different ways that the mind is not something separate from the body.[8] These approaches have been particularly influential in the sciences, especially in the fields of sociobiology, computer science, evolutionary psychology and the various neurosciences.[9][10][11][12] Other philosophers, however, adopt a non-physicalist position that challenges the notion that the mind is a purely physical construct. Reductive physicalists assert that all mental states and properties will eventually be explained by scientific accounts of physiological processes and states.[13][14][15] Non-reductive physicalists argue that although the brain is all there is to the mind, the predicates and vocabulary used in mental descriptions and explanations are indispensable, and cannot be reduced to the language and lower-level explanations of physical science.[16][17] Continued neuroscientific progress has helped to clarify some of these issues. However, they are far from having been resolved, and modern philosophers of mind continue to ask how the subjective qualities and the intentionality (aboutness) of mental states and properties can be explained in naturalistic terms.[18][19] * duty definition kant - GS Kant applied his categorical imperative to the issue of suicide in Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals,[3] writing that: A man reduced to despair by a series of misfortunes feels sick of life, but is still so far in possession of his reason that he can ask himself whether taking his own life would not be contrary to his duty to himself. Now he asks whether the maxim of his action could become a universal law of nature. But his maxim is this: from self-love I make as my principle to shorten my life when its continued duration threatens more evil than it promises satisfaction. There only remains the question as to whether this principle of self-love can become a universal law of nature. One sees at once that a contradiction in a system of nature whose law would destroy life by means of the very same feeling that acts so as to stimulate the furtherance of life, and hence there could be no existence as a system of nature. Therefore, such a maxim cannot possibly hold as a universal law of nature and is, consequently, wholly opposed to the supreme principle of all duty. *

*

Searches related to philosophy of suicide

*

Philosophy of suicide

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In ethics and other branches of philosophy, suicide poses difficult questions, answered differently by various philosophers.

[edit] Arguments against suicide

There have been many philosophical arguments made that contend that suicide is immoral and unethical. One popular argument is that many of the reasons for committing suicide – such as depression, emotional pain, or economic hardship – are transitory and can be ameliorated by therapy and through making changes to some aspects of one's life. A common adage in the discourse surrounding suicide prevention sums up this view: "Suicide is a permanent solution to a temporary problem." However, the argument against this is that while emotional pain may seem transitory to most people, and in many cases it is, in other cases it may be extremely difficult or even impossible to resolve, even through counseling or lifestyle change, depending upon the severity of the affliction and the person's ability to cope with their pain. Examples of this are incurable disease or severe, lifelong mental illness.[1]

__________________________________________________________________________________

Sunday, December 2, 2012

Marcus Aurelius: "Second, consider what kind of men they are at table, in bed, and so forth" - Comment: M.A. was quite interested in other men's sexual behaviors (regardless of their orientation) as one of the most important defining characteristics of their personalities, and rightly so.

The Thoughts of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus/General

Index

Affectation,vii. 60; viii. 30; xi. 18 (par. 9), 19. 18. [If any have offended against thee, consider first]: What is my relation to men, and that we are made for one another; and in another respect I was made to be set over them, as a ram over the flock or a bull over the herd. But examine the matter from first principles, from this. If all things are not mere atoms, it is nature which orders all things: if this is so, the inferior things exist for the sake of the superior, and these for the sake of one another (ii. 1; ix. 39; v. 16; iii. 4). Second, consider what kind of men they are at table, in bed, and so forth; and particularly, under what compulsions in respect of opinions they are; and as to their acts, consider with what pride they do what they do (viii. 14; ix. 34). Comment: M.A. was "straight", according to modern linguistic labelling system (apparently as much as it was possible to be "straight" in a sexually very liberal Ancient Rome). However this phrase indicates that he was quite interested in other men's sexual behaviors (regardless of their orientation) as one of the most important defining characteristics of their personalities, and rightly so. The deepest, most free and unburdened by the strings of social controls and "appropriate behaviors", aspects of personality, previous experiences, learned patterns and capacity for emotional sharing and interpersonal relationships are expressed in various and complex styles of sexual behaviors. Always a fruitful field for some students and practitioners of human behavior. |

![Olympic Wrestling is to be eliminated ... the IOC wants to drop wrestling starting with the 2020 Games. In Ancient Greece and Rome wrestling was an art. Plato, who wrestled himself, equated wrestling with dancing as one of the "manly arts." Plato (a Saint of @[181327751900550:274:Antinous the Gay God]) wrote in Book 7 of the "Nomoi" that wrestling should be mandatory for all men including scholars because "... the art of wrestling erect and keeping free the neck and hands and sides, working with energy and onstancy, with a composed strength, for the sake of health--these are always useful, and are not to be neglected, but to be enjoined alike on masters and scholars."](https://sphotos-a.xx.fbcdn.net/hphotos-ash3/s480x480/521813_545129848853670_1416632532_n.jpg)

![Photo: Today in History - 15/02 399 - Philosopher Socrates sentenced to death.

Socrates (pron.: /ˈsɒkrətiːz/; Greek: Σωκράτης, Ancient Greek pronunciation: [sɔːkrátɛːs], Sōkrátēs; c. 469 BC – 399 BC) was a classical Greek Athenian philosopher. Credited as one of the founders of Western philosophy, he is an enigmatic figure known chiefly through the accounts of later classical writers, especially the writings of his students Plato and Xenophon, and the plays of his contemporary Aristophanes. Many would claim that Plato's dialogues are the most comprehensive accounts of Socrates to survive from antiquity.

Through his portrayal in Plato's dialogues, Socrates has become renowned for his contribution to the field of ethics, and it is this Platonic Socrates who also lends his name to the concepts of Socratic irony and the Socratic method, or elenchus.

The latter remains a commonly used tool in a wide range of discussions, and is a type of pedagogy in which a series of questions are asked not only to draw individual answers, but also to encourage fundamental insight into the issue at hand. It is Plato's Socrates that also made important and lasting contributions to the fields of epistemology and logic, and the influence of his ideas and approach remains strong in providing a foundation for much western philosophy that followed.

Trial and death

Socrates lived during the time of the transition from the height of the Athenian hegemony to its decline with the defeat by Sparta and its allies in the Peloponnesian War. At a time when Athens sought to stabilize and recover from its humiliating defeat, the Athenian public may have been entertaining doubts about democracy as an efficient form of government. Socrates appears to have been a critic of democracy, and some scholars[who?] interpret his trial as an expression of political infighting.

Claiming loyalty to his city, Socrates clashed with the current course of Athenian politics and society. He praises Sparta, archrival to Athens, directly and indirectly in various dialogues. One of Socrates' purported offenses to the city was his position as a social and moral critic. Rather than upholding a status quo and accepting the development of what he perceived as immorality within his region, Socrates questioned the collective notion of "might makes right" that he felt was common in Greece during this period. Plato refers to Socrates as the "gadfly" of the state (as the gadfly stings the horse into action, so Socrates stung various Athenians), insofar as he irritated some people with considerations of justice and the pursuit of goodness. His attempts to improve the Athenians' sense of justice may have been the source of his execution.

According to Plato's Apology, Socrates' life as the "gadfly" of Athens began when his friend Chaerephon asked the oracle at Delphi if anyone was wiser than Socrates; the Oracle responded that no-one was wiser. Socrates believed that what the Oracle had said was a paradox, because he believed he possessed no wisdom whatsoever. He proceeded to test the riddle by approaching men considered wise by the people of Athens—statesmen, poets, and artisans—in order to refute the Oracle's pronouncement.

Questioning them, however, Socrates concluded that, while each man thought he knew a great deal and was wise, in fact they knew very little and were not wise at all. Socrates realized that the Oracle was correct, in that while so-called wise men thought themselves wise and yet were not, he himself knew he was not wise at all, which, paradoxically, made him the wiser one since he was the only person aware of his own ignorance.

Socrates' paradoxical wisdom made the prominent Athenians he publicly questioned look foolish, turning them against him and leading to accusations of wrongdoing. Socrates defended his role as a gadfly until the end: at his trial, when Socrates was asked to propose his own punishment, he suggested a wage paid by the government and free dinners for the rest of his life instead, to finance the time he spent as Athens' benefactor. He was, nevertheless, found guilty of both corrupting the minds of the youth of Athens and of impiety ("not believing in the gods of the state"), and subsequently sentenced to death by drinking a mixture containing poison hemlock.

According to Xenophon's story, Socrates purposefully gave a defiant defense to the jury because "he believed he would be better off dead". Xenophon goes on to describe a defense by Socrates that explains the rigors of old age, and how Socrates would be glad to circumvent them by being sentenced to death. It is also understood that Socrates also wished to die because he "actually believed the right time had come for him to die."

Socrates' death is described at the end of Plato's Phaedo. Socrates turned down the pleas of Crito to attempt an escape from prison. After drinking the poison, he was instructed to walk around until his legs felt numb. After he lay down, the man who administered the poison pinched his foot. Socrates could no longer feel his legs. The numbness slowly crept up his body until it reached his heart. Shortly before his death, Socrates speaks his last words to Crito: "Crito, we owe a rooster to Asclepius. Please, don't forget to pay the debt." Asclepius was the Greek god for curing illness, and it is likely Socrates' last words meant that death is the cure—and freedom, of the soul from the body. Additionally, in Why Socrates Died: Dispelling the Myths, Robin Waterfield adds another interpretation of Socrates' last words. He suggests that Socrates was a voluntary scapegoat; his death was the purifying remedy for Athens’ misfortunes. In this view, the token of appreciation for Asclepius would represent a cure for the ailments of Athens. Source & References : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Socrates#Trial_and_death](https://sphotos-b.xx.fbcdn.net/hphotos-ash3/c231.0.403.403/p403x403/13102_505566059485176_1832811798_n.jpg)

This is a quotation from John Donne (1572-1631). It appears in Devotions upon emergent occasions and seuerall steps in my sicknes - Meditation XVII, 1624:

This is a quotation from John Donne (1572-1631). It appears in Devotions upon emergent occasions and seuerall steps in my sicknes - Meditation XVII, 1624: